The forecast is warmer and weirder

Justin Gillis and Joanna M. Foster

April 1, 2012 Crazy climate ... does science have a clue what is going on? Photo: Nick Moir

Crazy climate ... does science have a clue what is going on? Photo: Nick MoirSome people call what has been happening across the northern hemisphere in the past few years ''weather weirding'' and March turned out to be a fine example. As a surreal heatwave was peaking across much of the US last week, pools and beaches drew crowds, some farmers planted their crops six weeks early and trees burst into bloom.

''The trees said, 'Aha! Let's get going!''' says Peter Purinton, a maple syrup producer in Vermont. ''Spring is here!''

Now a cold snap in the northern states has brought some of the lowest temperatures of the season, with damage to tree crops alone likely to be in the millions of dollars.

Advertisement: Story continues below

Lurching from one weather extreme to another seems to

have become routine. Parts of the US may be shivering but Scotland is

setting heat records. Across Europe, hundreds of people died during a

severe cold wave in the first half of February but a week later

revellers in Paris were strolling on the Champs-Elysees in shirt

sleeves.Does science have a clue what is going on? The short answer appears to be: not quite.

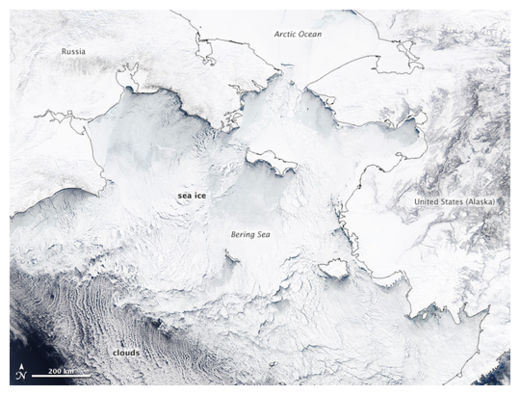

The longer answer is that researchers are developing theories that, should they withstand scrutiny, may tie at least some of the erratic weather to global warming. Suspicion is focused on the drastic decline of Arctic sea ice, believed to be a direct consequence of the human release of greenhouse gases.

''The question really is not whether the loss of the sea ice can be affecting the atmospheric circulation on a large scale,'' says Jennifer Francis, a Rutgers University climate researcher. ''The question is, how can it not be and what are the mechanisms?''

As the planet warms, many scientists say, more energy and water vapour enter the atmosphere and are driving weather systems.

''The reason you have a clothes dryer that heats the air is that warm air can evaporate water more easily,'' says Thomas C. Peterson, a researcher with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. A report released last week by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the UN body that issues periodic updates on climate science, confirmed a strong body of evidence links global warming to an increase in heatwaves, heavy rainfall and other precipitation and more frequent coastal flooding.

''A changing climate leads to changes in the frequency, intensity, spatial extent, duration and timing of extreme weather and climate events, and can result in unprecedented extreme weather and climate events,'' it says.

US government scientists recently reported that February was the 324th consecutive month in which global temperatures exceeded their long-term average for a given month; the last month with below-average temperatures was February 1985. In the US, many more record highs are being set at weather stations than record lows, a bellwether indicator of warming.

So far this year, the US has set 17 daily highs for every daily low, according to an analysis performed by the New Jersey research group Climate Central. Last year the country set nearly three highs for every low. But, while the link between heatwaves and global warming may be clear, the evidence is much thinner regarding types of weather extremes.

Scientists studying tornadoes are plagued by poor statistics that could be hiding significant trends but so far they are not seeing a long-term rise in the most damaging twisters.

And researchers studying specific events such as the Russian heatwave of 2010 have often come to conflicting conclusions about whether to blame climate change.

Scientists who dispute the importance of global warming have long ridiculed attempts to link greenhouse gases to weather extremes. John Christy, a climate scientist at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, told the US Congress last year ''weather is very dynamic, especially at local scales, so that extreme events of one type or another will occur somewhere on the planet every year''.

Yet mainstream scientists are determined to figure out which climate extremes are being influenced by human activity and their attention is increasingly drawn to the Arctic sea ice.

Because greenhouse gases are causing the Arctic to warm more rapidly than the rest of the planet, the sea ice cap has shrunk about 40 per cent since the early 1980s: an area of the Arctic Ocean the size of Europe has become dark, open water in the summer instead of reflective ice, absorbing extra heat and releasing it to the atmosphere in autumn and early winter.

Francis, of Rutgers, has presented evidence that this is affecting the jet stream, the huge river of air that circles the northern hemisphere in a meandering fashion. Her research suggests the declining temperature contrast between the Arctic and the middle latitudes is causing kinks in the jet stream to move from west to east more slowly and that those kinks have everything to do with the weather in a particular spot.

''This means that whatever weather you have today - be it wet, hot, dry or snowy - is more likely to last longer than it used to,'' says Francis, who recently published a paper on her theory. ''If conditions hang around long enough, the chances increase for an extreme heatwave, drought or cold spell to occur.'' But the weather can change rapidly once the kink moves along.

Not all of her colleagues buy that explanation. Martin Hoerling, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration researcher, agrees that global warming should be taken seriously but contends some researchers are in too much of a rush to attribute specific weather events to human causes. Hoerling says he has run computer analyses that failed to confirm a widespread effect outside the Arctic from declining

sea ice. ''What's happening in the Arctic is mostly staying in the Arctic,'' he says and suspects that future analyses will find the magnitude of this month's heatwave to have resulted mostly from natural causes but concedes, ''It's been a stunning March.''

That's certainly what farmers have thought. Purinton has been tapping maple trees for 46 years. This year he tapped the trees two weeks earlier than usual, a consequence of the warm winter.

But when the heatwave hit the trees budded early, which tends to ruin the syrup's taste. That forced him to stop four weeks earlier and halved his typical production.

''Is it climate change? I really don't know,'' he says. ''This was just one year out of my 46 but I have never seen anything like it.''

Read more: http://www.smh.com.au/environment/weather/the-forecast-is-warmer-and-weirder-20120331-1w50o.html#ixzz1rOusUKpx

''I think we are more likely to see leadership out of China than America" ... Malcolm Turnbull. Photo: Alex Ellinghausen

''I think we are more likely to see leadership out of China than America" ... Malcolm Turnbull. Photo: Alex Ellinghausen